Academic Integrity

A page within Oral History Program

College Studentness: the living, working, social, and emotional conditions associated with being a college student at UW-La Crosse, from 1909 to the present day.

Figuring Out the History of Academic Honesty at UWL: Work-In-Progress

Typically we use our weekly blogs for the “College Life: What We Remember” project to highlight oral history clips that relate to the weekly themes of UWL’s FYS 100 curriculum. But there are some weekly themes that we don’t have relevant oral history evidence for – yet! The FYS 100 topic for Week 5, Academic Integrity, is one of these cases. So we’ve decided to do three things: acknowledge this blog post is definitely a work-in-progress, describe what existing primary sources suggest so far, and invite former UWL college students to share their stories with us so we can build a better picture of the history of academic integrity at UWL ca. 1909 - present day.

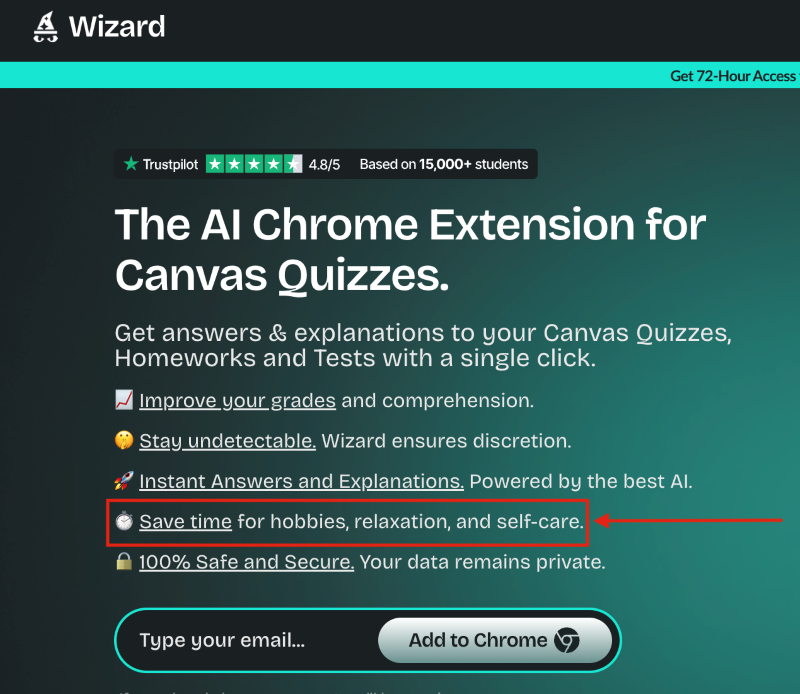

One of the key themes emerging from the "College Life: What We Remember" oral histories is that effectively navigating college studentness takes work, time, and practice. Yet all of the competing demands on students' time can make it hard to fit in everything someone might hope to include in a "balanced" life. In the 2020s, language about work-life balance is often used to help market cheating services like the AI plug-in below, which claims it can take Canvas quizzes for someone while leaving them more time for "hobbies, relaxation, and self-care." The service's claim that the AI plug-in would let a user "stay undetectable" highlights how both the company and its potential clients are aware it is unethical to use the service for an assignment. (Why would its use need to be hidden?) But the case being made for the plug-in's benefit -- saving time -- works as evidence of one of the biggest challenges for college students: making time and space for all of their academic responsibilities.

Web Advertisement for AI Quiz-Completion Service, 2024

Web Advertisement for AI Quiz-Completion Service, 2024

In our "College Life" oral history project we haven't yet been able to learn much about how former college students thought about academic integrity challenges, how they felt when they realized classmates were cheating, or how available technologies and practices for cheating worked in the pre-AI world. So in this blog post, we're sharing two other kinds of primary source evidence: two short audio clips that help us envision the pressures on students, and written sources (newspaper articles, honor code sections, email) that offer insight into the evolution of academic honesty challenges from the 1990s to the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, we have two brief hints of the complex academic situation former college students at UWL have faced. Troy describes his heavy course load in his junior and senior years (18 credits) while meeting requirements for his new major after transferring back to UWL. Then Peter describes being the kind of student who needed every minute of an exam period to do their best work. Troy and Peter's perspectives help us envision some of the different time challenges (lots of classes each semester, limited minutes to complete a graded activity) associated with college studentness. Peter also hints at another factor that might impact academic integrity: how well you think your professors know you as an individual.

Troy (first year: 1984)

Clip Length: 0:34

Transcript

Troy: Because I needed credits. It was already taking me five years plus three summers to get through [it] all, cause again, with the Education credits and the Social Studies credits, it was a massive amount, I think I graduated with like 170 some credits. Which again, I don’t think my parents appreciated all the extra time in school. But most semesters, I was taking 18 credits. Some semesters I asked for an overload to take 19. And that was also trying to do the field experiences where you’re going out into the schools.

Peter (first year: 1984)

Clip Length: 1:45

Transcript

Peter: If I was prepared for a class. I was always the very last person that left that exam. I needed the whole time plus more. And you know I was never tested, for you know, having learning disabilities at all. But to get more time I was tested, and I don't remember what I qualified for, but it gave me the ability to have in most cases as much time as I needed to take a test. So that was that was huge, helping me out.

Brenna: Right? Yeah, I'm sure for sure. Was there anything else then that your professors did to help you out with that? Or Was there anything you had to do for yourself to like? Get there and to work harder, I guess.

Peter: And I also learned, Build a relationship with your professors, because if you have a relationship with your professor, they're going to fight for you. They're gonna know that you are there to learn. And that's something I passed on to my kids, I said. You know, no matter where you're at. Make sure that professor or the teacher, or whatever knows you. If they know you, they're going to be working out for you. You know just you know someone that they see and don't really know where you're at.

Brenna: Yeah, Absolutely. No. I think that's that's great advice. I've definitely noticed that over the years when I was more in my Gen. eds. Not really knowing my professors to now being in a set major where you have the same professors kind of in it, it is very beneficial to create those relationships with them, for sure.

Acknowledging Academic Misconduct at UWL, ca. 1990s - 2020s

Our "College Life" oral history interview conversations have not uncovered any clarifying evidence about the history of academic integrity concerns, reactions to cheating, or attempts to address grey areas about assignments were completed at UWL in past decades. We're admitting we're reading against the grain when referencing these two short comments by interviewees (Troy and Peter) whose college careers were guided by academic integrity. All their evidence tells us is that college students faced intense academic situations.

A different kind of primary source helps us envision what the academic integrity climate might have been like in previous decades. On April 15 1996, The La Crosse Tribune published an article about a student movement on the UWL campus to create a student honor code. That highlighted a finding from a 1994 campus "Self-Study Steering Report" based on anonymous surveys completed by 1000 UWL students. The survey indicated that 40% of respondents had witnessed some form of cheating or dishonest behavior associated with coursework among their peers. A December 7, 1995 UWL student newspaper article (The Racquet), fills in the backstory for why UWL students might have been motivated to create a student honor code in the mid-1990s: participants in a panel discussion earlier that week pointed out that at that time on campus definitions of what constituted "cheating" were murky and varied from person to person. The present-day UWL student honor code statement seems to trace its origins to these mid 1990s campus discussions. You can read the text of the current honor code statement below -- see #6 in our list of primary sources below.

So far our discussion has hinted at continuities related to academic integrity that might connect college studentness across multiple generations: challenges related to time and juggling competing priorities, the ways that what is, or isn't, cheating might seem murky. But we also need to acknowledge an important change, or turning point, in this story: disruptions to face-to-face learning caused by the COVID-19 pandemic starting in mid-March 2020. One kind of primary source evidence that hints at how the scope of cheating may have changed in Spring semester 2020 is an email that UWL professors received on August 12, 2020 -- see #5 in our list of primary sources below. The email summarized data about documented academic honesty violations professors alerted the Student Life Office to between September 1, 2019 and June 14, 2020. While there were 10 instances of documented cheating between September and the last day before campus closed because of COVID-19 (March 14, 2020), there were 45 instances of documented cheating reported during the second half of Spring 2020.

As the above statistics from 2020 and the marketing of AI cheating devices like the one pictured at the start of our blog suggest, we seem to be living in a different academic integrity context these days?

Additional Primary Sources

How Alumni Can Help

OHP definitely views our work as a collaborative effort. And we especially need evidence and guidance about subjects where our research is still very much a work-in-progress like perceptions of academic integrity. There are two distinct ways former college students at UWL can help the “College Life: What We Remember” project.

- Share what you remember by participating in an oral history interview. History continuously evolves as more information is brought to light. Our “College Life: What We Remember” oral history project is in its early stages: right now we only have 15 interviews. In Fall 2024 and Spring 2025 we’ll be conducting another round of interviews. Do you have memories about your college years at UWL you’d be willing to share with our project? We’re hoping to learn more about multiple aspects of college life. But as you can see from this blog post, we’re especially hoping to learn about how former college students thought about academic integrity challenges, how they felt when they realized classmates were cheating, or how available technologies and practices for cheating worked in the pre-AI world. If you’re interested in participating in an oral history interview, please fill out this online survey to let us know. You can also contact us at oralhistory@uwlax.edu to find out more about the “College Life” oral history project.

- Make a financial donation to sustain our project. OHP relies on donations to fund our student internships and keep our oral history work going. You can make a gift online through this link: Donate to OHP.

Production credits: writing by Tiffany Trimmer and Shaylin Crack, research and conceptualization by Shaylin Crack, web design by Olivia Steil, collection processing by Shaylin Crack, Julia Milne, and Isaac Wegner.