Chapter 1: The Case for Growth

A page within Menard Family Initiative

In the first chapter of Onward Wisconsin, Russel S. Sobel and J. Brandon Bolen make the case for economic growth in the state of Wisconsin. They argue that Wisconsin’s current economic policies have failed to harness the state’s potential for economic development and prosperity. Wisconsin ranks 26th among the states in per capita personal income at only 93 percent of the national average. Compared to neighboring Illinois and Minnesota, Wisconsin performs significantly worse on this measure, amounting to a shortfall of more than $6,000 in per capita income.

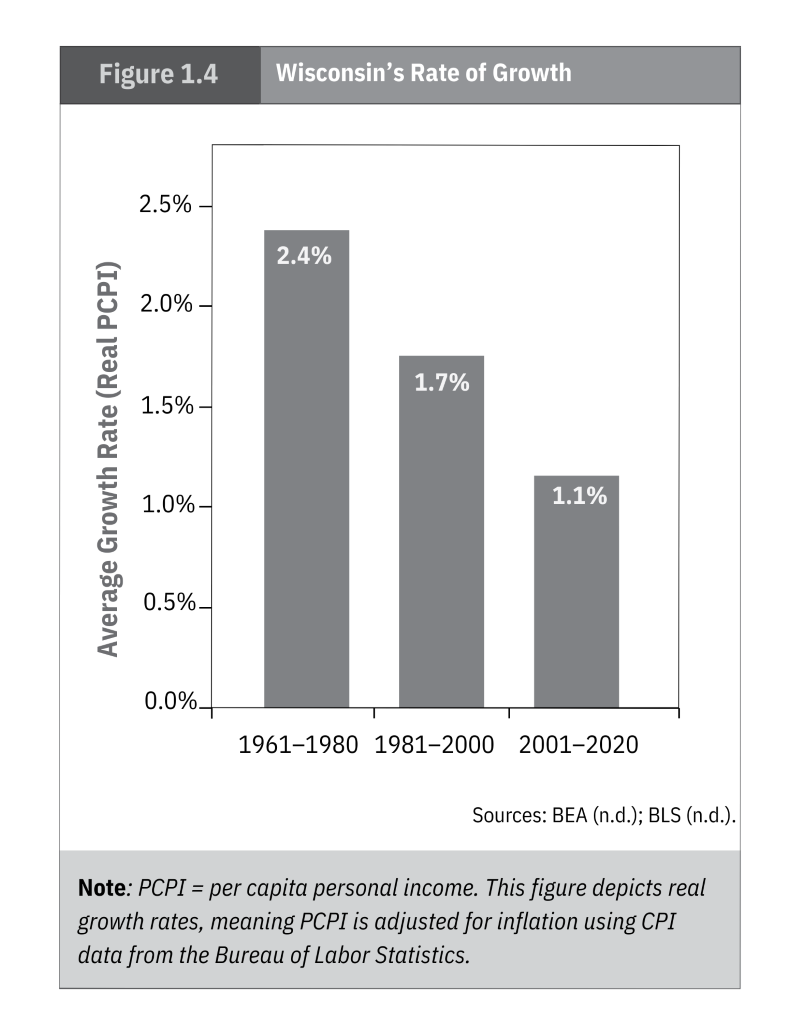

The authors point out that Wisconsin’s per capita income has not always been subpar. In fact, the state has ranked as high as 19th on this measure on multiple occasions in its history. As of 2020, however, the state is ranked just above its historical low of 27th. The authors stress that, although Wisconsin’s underperformance is substantial, it is the result of only a small discrepancy between its rate of economic growth and those of other states. As the authors show in Figure 1.4, the decline in Wisconsin’s ranking on per capita income can be attributed to its relatively poor growth rate of 1.1 percent between 2000 and 2020.

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.4

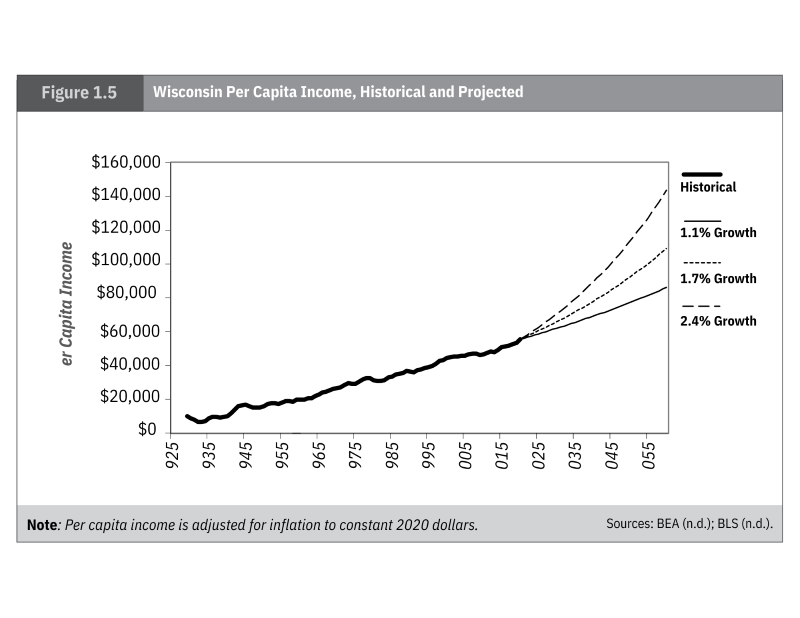

In Figure 1.5 the authors project Wisconsin’s future per capita income based on the three historical growth rates showcased in Figure 1.4. Using this projection, the authors show how significant a small change in growth rates can be in determining standards of living in the long run. For example, a mere 0.6 percentage point increase in growth rates could mean a difference of many thousands of dollars in per capita income after just a couple of decades.

Figure 1.5

Figure 1.5

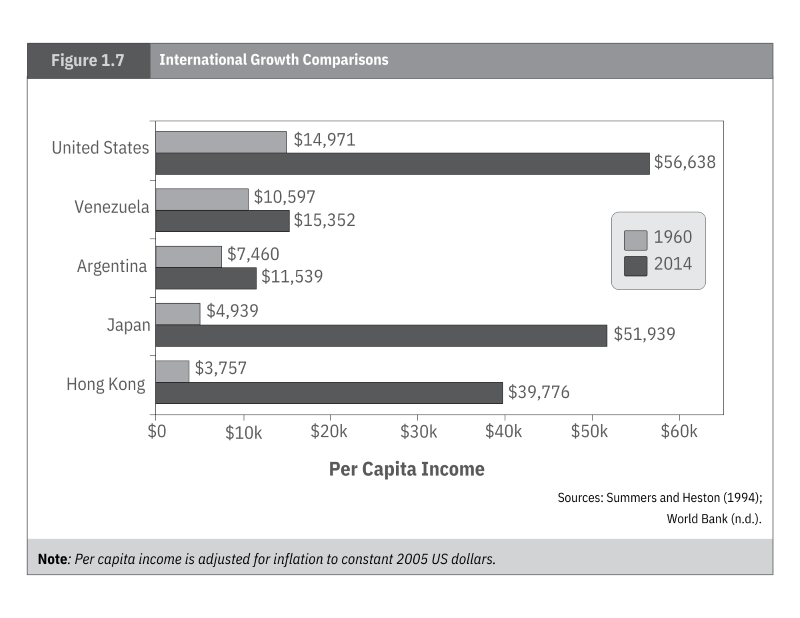

The authors then discuss how several other states, such as Wyoming and the Dakotas, achieved significant gains in per capita income in just 15 years by sustaining relatively higher rates of economic growth. The authors further discuss how such small differences in rates of economic growth explain the wealth and poverty of nations. In Figure 1.7, they show how Japan and Hong Kong – despite being much poorer than countries like Venezuela and Argentina in 1960 – became some of the wealthiest in world over the following four decades.

Figure 1.7

Figure 1.7

This difference in outcomes is again due to discrepancies in growth rates. During this period, Hong Kong and Japan achieved growth rates of about 4.5 compared to less than one percent for Venezuela and Argentina. As a result, the latter two nations have achieved relatively minimal gains in standards of living compared to the former two.

Finally, the authors discuss how the benefits of higher economic growth go far beyond increases in a state’s per capita income. They show that citizens living in states with higher incomes tend to live longer, safer, and healthier lives; are more likely to graduate from high school and acquire college education; and are less likely to divorce or suffer from mental illness.