Chapter 3: Why Capitalism Works

A page within Menard Family Initiative

In Chapter 3, Sobel and Bolen dive deeper into how the process of capitalism leads to economic growth. First, they explain how wealth is created through production and exchange; When a good or service is produced and sold to a consumer, it generates both producer and consumer surplus. In other words, voluntary exchanges create wealth by making both parties better off. Thus, policies that enable more of such exchanges to occur will increase a society’s wealth.

Next, the authors articulate how the entrepreneurial process enables the discovery of new means of creating wealth through voluntary exchange. This process entails the invention of new ways to combine society’s scarce resources for productive use. However, they clarify that, under a capitalist system, not all new combinations of resources will be successful. Through the profit and loss system of a capitalist economy, uses of resources that do not create value for society will fail, while those that do will succeed. Thus, as the authors state, “a vibrant economy will have both a large number of new business start-ups and a large number of failures.” Not only do some new businesses fail along the discovery process, but formerly successful businesses may be eliminated as well. This process is known as “creative destruction,” a term coined by the well-known economist Joseph Schumpeter. A thriving economy – in which less productive uses of resources are discontinued while more productive uses succeed – is possible when entrepreneurs are free to participate in the market and test their ideas.

Sobel and Bolen then explain how a capitalist system coordinates and employs resources to their most productive ends without the need for centralized planning. Through the market process, prices serve as signals – which contain information about buyer preferences, relative scarcity, and production costs – that guide individual choices towards the exchanges that create the most value. A key aspect of this market price system is its spontaneous and decentralized nature, as famously established by Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek. The price system is spontaneous in that it is the “result of human action but not human design.” As the authors argue, when a system arises naturally as such, it will be more likely to satisfy the true preferences of those who inadvertently participate in its creation and thus create the most value. The price system is decentralized in that the knowledge necessary for its coordination is not ascertainable by any individual or group of individuals, but instead exists distributed amongst the minds of all those participants involved in its creation. This decentralized nature clarifies why government policy cannot serve as an effective alternative to the price system; While markets can convey information through prices, such information is unavailable to policymakers and is unusable in government programs which lack the price mechanism. Because policymakers cannot ascertain the ever-changing, decentralized knowledge that exists amongst their constituents, policies that are developed with good intentions often lead to unintended consequences and potentially worse outcomes overall. Further, as the authors note, “there is no profit-and-loss-type system to eliminate bad polices over time.” Thus, they argue that the capitalist system should not be unfairly compared to hypothetical centrally planned alternatives that are inherently impracticable due to the knowledge problem.

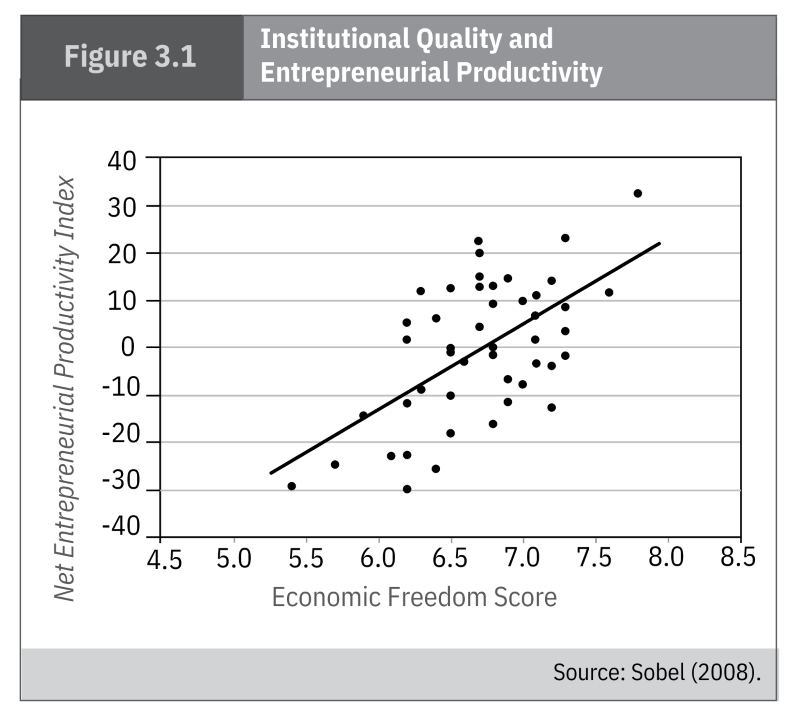

Finally, the authors discuss how government interference in the market process can create unproductive entrepreneurship in which – rather than creating new combinations of resources that increase a society’s net-wealth – businesses utilize resources for the purpose of acquiring government favors, subsidies, or tax breaks. Since such government assistance would be paid for by taxes – which create distortions of their own and diminish economic activity – and do not generate new wealth, they lead to an overall reduction in a society’s wealth. Figure 3.1 illustrates the relationship between states’ economic freedom scores and their net entrepreneurial productivity, “where productive entrepreneurship is measured relative to unproductive political and legal entrepreneurship.” As can be seen, states with greater economic freedom have higher net entrepreneurial productivity.

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

On net entrepreneurial activity, Wisconsin ranked 36th in the United States. While the state ranked 25th on productive entrepreneurship, it ranked 7th on unproductive entrepreneurship. To discourage such unproductive entrepreneurial activity, Sobel and Bolen provide a list of suggested state policy reforms which can be found in the complete chapter.