Chapter 6: Improving Wisconsin Education with School Choice

A page within Menard Family Initiative

In chapter 6, Will Flanders discusses private alternatives to public education in Wisconsin. The basic argument for private educational alternatives is based on the same profit-and-loss mechanism discussed in Chapter 3. Unlike public schools, private schools must compete amongst each other for students and are thus incentivized to provide higher quality educational services. Because taxpayers already pay for the administration of public schools, families opting for a private alternative would effectively pay twice for one education. As a result, public schools essentially have a monopoly on the provision of education.

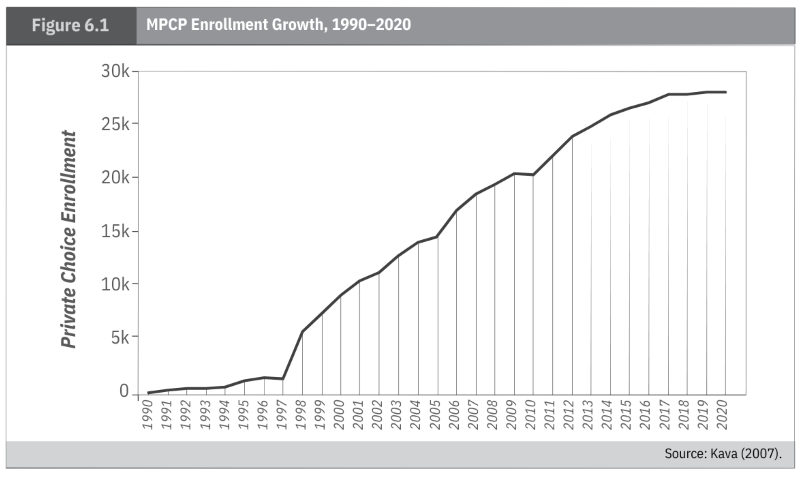

In 1990, Milwaukee became the first city to develop a program – the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP) – to provide families with vouchers allowing them to attend private schools using public funding. After some time, the program’s enrollment limits were removed and income limits were increased, leading to a dramatic rise in the number of students enrolled in private schools using MPCP vouchers, as shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1

In 2013, private school choice became available statewide through the Wisconsin Parental Choice Program (WPCP).

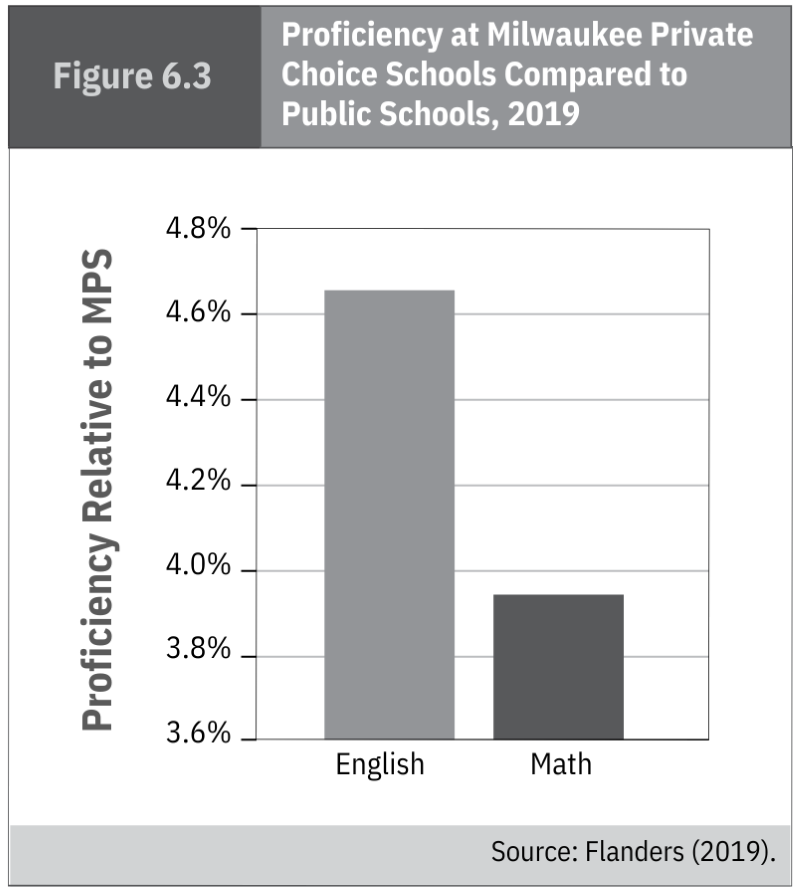

To evaluate the impacts of school choice on student outcomes, Flanders reviews the existing research, including his own. In one study, Flanders compares MPCP students’ English and math proficiency to that of public-school students while controlling for various student characteristics such as poverty, race, and English-language-learner status. He finds that MPCP students are more proficient in both subjects, as indicated by Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3

Figure 6.3

Research also shows that “MPCP students were 5 percentage points more likely than similar students in public schools to enroll in college. These students were 38 percent more likely to graduate from college than students in the public-school sample.” Furthermore, research has been conducted on the impact of school choice on student character and civic engagement, finding that MPCP students appear more tolerant, are more likely to vote, and more likely to have volunteered. Additional research finds that “MPCP students were 53 percent less likely to have been convicted of a drug crime, 86 percent less likely to have been convicted of a property crime, and 38 percent less likely to have been involved in a paternity lawsuit.”

One argument in favor of school choice is that the competitive pressures it creates may entice public schools to improve as well. In reviewing the evidence for this argument, Flanders finds that “Of 26 studies that have investigated this topic, 24 have found a positive effect on public-school performance, 1 found a neutral effect, and 1 found a negative effect (in Florida).”

Additionally, to examine how well the market mechanism works for school choice, Flanders co-authored a study exploring whether families make decisions based on school quality, as measured by test scores. They found that “schools in the MPCP that had higher scores on the state exam were growing more quickly than schools that had lower test scores” and that “lower-performing choice schools were more likely to close or to leave the program than public schools with similar performance levels.”

Next, Flanders debunks several common myths about private school choice. Regarding costs, he points out that school choice has saved Wisconsin taxpayers money as choice schools tend to spend less per student than public schools. Regarding self-selection of the best students into choice schools, he clarifies that “choice-participating schools must take all applicants. If an excessive number of students apply to a particular school, a lottery must be held for admission.” Regarding choice school accountability, Flanders claims that – in addition to parents’ and families’ expectations – Wisconsin’s choice schools are also held to especially high regulatory standards.

Next, Flanders discusses other forms of school choice, including charter schools, open enrollment, and tuition tax credits. Charter schools are public schools that are facilitated by entities external to the school district. Open enrollment is a program that allows public school students to transfer from one district to another when space is available. Tuition tax credits allow “families to deduct up to $4,000 for grades K–8 and $12,000 for grades 9–12 from their state income tax.” Finally, Flanders provides the following list of recommended policy reforms to enhance the school choice landscape in Wisconsin, with further details available in the full chapter:

- Remove – or at least equalize – income limits on school choice programs.

- Move toward student-centered funding.

- Remove institutional barriers to choice.

- Improve the environment for charter schools.

- Move towards education savings accounts.