Chapter 8: Legal Reforms to Improve Economic Development and Growth in Wisconsin

A page within Menard Family Initiative

In Chapter 8, Anthony LoCoco suggests several legal reforms that would establish more reliable institutions, reduce costs for individuals and businesses, and enable greater economic growth in Wisconsin.

First, he discusses the 2011 enactment and subsequent undermining of Wisconsin Act 21. A key provision of Act 21 is its requirement that state agencies “identify explicit authorization in a statute or rule before engaging in certain regulatory activity.” As the author argues, this law “supports economic growth by reining in overregulation of small businesses by regulatory agencies too quick to find authority where it does not exist.”

Unfortunately, following legal challenges by the state’s Department of Natural Resources, the Wisconsin Supreme Court restored agencies’ “ability to rely on vague and broadly worded delegations of power to support regulatory actions not clearly authorized by statute.” Effectively, the court drew a distinction between “explicit” and “specific” authority. For Act 21 to achieve its originally intended purpose, LoCoco argues that it should be amended to require that agencies identify explicit and specific authority that supports its actions.

Next, the LoCoco discusses the need for greater protection of economic freedom in Wisconsin by its state constitution. He claims there are two ways to achieve this goal. The first is to obtain a state court decision extending constitutional protection to economic freedom. However, this approach has been attempted in the past without success. The second approach is to amend the state constitution to recognize “the right to earn a living in any lawful occupation without unnecessary government interference.” LoCoco explains that, in contrast with amendments to the United States Constitution, amendments to the constitution of Wisconsin can be made relatively easily. To be implemented, “a suggested amendment must obtain a majority vote of two successive state legislatures and then approval in a statewide referendum.”

LoCoco then discusses the need to reduce the financial burden of litigation for individuals and businesses in cases involving the Wisconsin government. Currently, the Wisconsin Equal Access to Justice Act (WEAJA) allows certain individuals and businesses to recoup attorney fees if they prevail in particular types of litigation involving a state agency. However, the law only applies in cases where an agency initiates the litigation. Thus, in successful cases in which an individual or business initiates litigation, the WEAJA provides no compensation for attorney fees. LoCoco recommends the law be amended to “apply to actions by or against state agencies.” Additionally, the WEAJA also denies compensation when the agency’s position is “substantially justified,” meaning it had reasonable basis in law and fact. LoCoco argues that this bar for withholding compensation should be raised. Next, he points out that the WEAJA has income and business size limits, preventing some individuals and businesses from deserved relief when they prevail in cases involving state agencies. LoCoco argues that these limits should be expanded, not only to prevent injustice but also to penalize the government for initiating litigation in error.

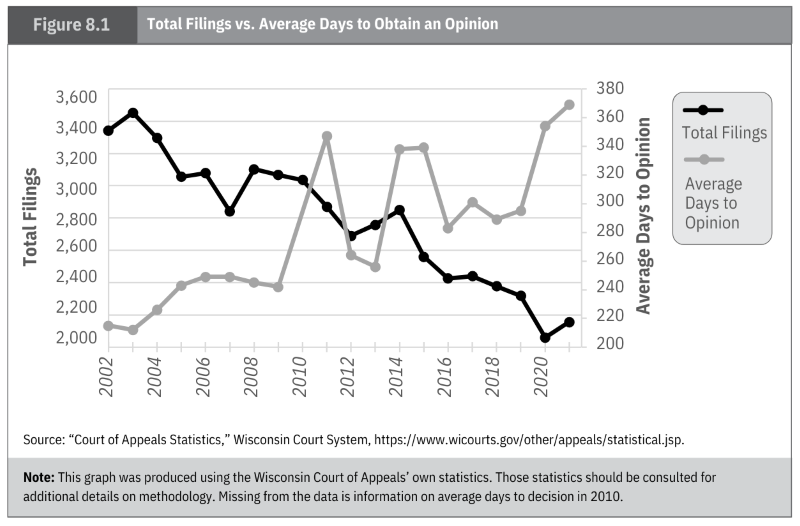

Finally, LoCoco discusses the need to reform Wisconsin’s court of appeals, whose “chief role is to correct errors in the decisions of circuit courts.” This court currently consists of 16 judges seated among four districts; an arrangement that has not been updated since 1994. As a result, the average time before an opinion is made has risen to 369 days as of 2021, as shown in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1

Figure 8.1

However, as LoCoco points out, wait times are even longer for decisions by more than a single justice. In 2021, a three-judge opinion took an average of 490 days and an opinion by the entire court – per curiam – took an average of 534 days. These delays create significant uncertainty and costs for individuals and businesses in Wisconsin, hindering economic growth. To address this issue, LoCoco’s final policy recommendation is to expand and redistrict the court of appeals to better distribute its caseload amongst judges.