Chapter 9: A Road Map for Market-Based Health Care Reform in Wisconsin

A page within Menard Family Initiative

In Chapter 9, Daniel Sem and Scott Niederjohn discuss the economics of health care markets and the tradeoffs associated with reforming them.

First, they discuss the demand for health care. Because resources that can be used in the production of health care services are scarce, tradeoffs must be made and, as a result, consumers’ desire for more health care will never be completely satiated. This is true whether health care is paid for by consumers or by government. However, a key difference between the demand for healthcare and most other goods is that the former tend to be necessities with few available substitutes. As a result, the demand for health services tends to be inelastic, meaning that a change in price leads to a relatively small change in quantity demanded. Additionally, healthcare services are normal goods, meaning that spending on them will increase as consumer incomes increase.

A primary factor distinguishing the demand for healthcare from that of other goods, however, is that most payments for healthcare in the United States are made through third party insurance companies. As a result, it is uncommon for consumers of health care to “shop around” for the best deal when the service they receive is covered by their insurance, especially in cases of emergency. Another distortion in the market for health care is that insurance is often provided to employees as a form of compensation due to the tax-exempt status of employer-provided health insurance.

Furthermore, since most medical practitioners are compensated on a fee-for-service basis, they have little incentive to economize on their provision of services. Additionally, the threat of malpractice suits creates a further incentive for doctors to prescribe unnecessary medical services to protect themselves from liability. This incentive structure does not harm the typical doctor-patient relationship, however, as payments for unnecessary services will typically be made by a patient’s insurance, rather than “out-of-pocket.”

Next, the authors discuss the supply side of the health care market. A key contributor to the high costs of health services is the scarcity of physicians. The length and cost of a medical education is a meaningful impediment to the supply of doctors. Additionally, the health care industry is part of the more service-oriented sector of the economy and thus requires a great deal of human labor. As a result, it has not been able to achieve the same productivity gains from automation as industries in the manufacturing sector. Furthermore, as the authors point out, stringent regulations on the health care industry lead to slow adoption of new medical technologies.

Taking both supply and demand into account, “health care suffers from being provided outside the context of a vibrant free-market system. Health care policies that shift costs heavily to third-parties have eroded the incentive for consumers and providers to economize.” Likewise, the market for health care suffers greatly from a lack of price transparency. As the authors put it: “In most cases patients undertake a treatment with little idea of how much it costs.”

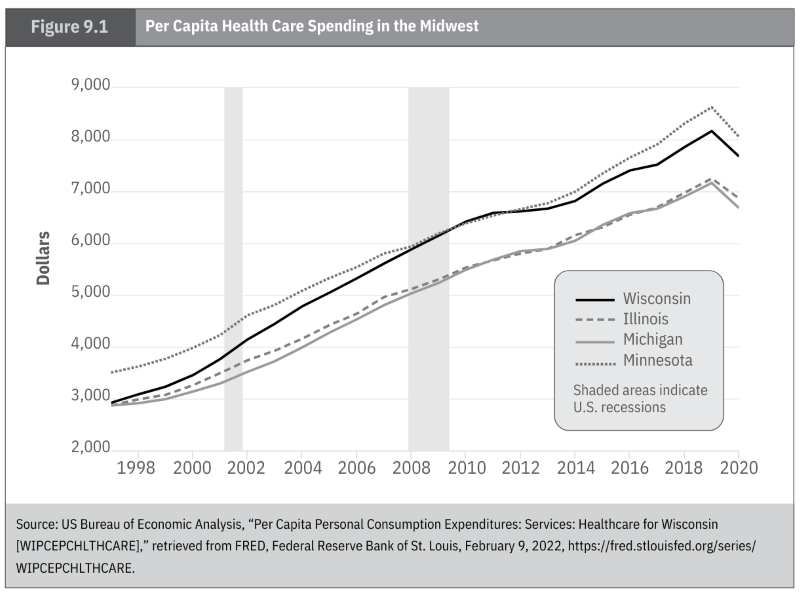

Sem and Niederjohn then discuss Arnold Kling’s description of the healthcare market as a trilemma in which only two of three goals – affordability, access, and insulation from risk – can be achieved. Different nations have chosen different pairs of these goals in designing their healthcare systems. In the British and Canadian systems in which taxes pay for universal, single-payer health care, affordability and insulation from risk are prioritized. As a result, direct costs to patients are low. However, this comes at the cost of long queues and extensive wait times, effectively limiting access. The American system, on the other hand, prioritizes access and risk mitigation at the cost of especially high prices. In the Midwest, for example, health care spending per person has dramatically increased over the past two decades or so, as indicated by Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1

Figure 9.1

Next, Sem and Niederjohn discuss direct primary care (DPC), a novel solution to the health care costs in the United States in which patients pay a monthly membership fee to have direct access to a primary care physician. As they explain, this solution can provide patients with “affordable, accessible, and better care for over 90 percent of common medical problems.” Finally, the authors provide a list of principles for health care reform:

- Consumers should be able to choose amongst providers and services.

- Insurance should primarily cover large, unanticipated expenses rather than routine procedures.

- Consumers should always have access to private insurance options and their insurance should not be tied to their employment.

- Policymakers should bolster tax-advantaged health savings accounts and encourage new compensation models like DPC.

- Medicare and Medicaid dollars should be provided via vouchers, allowing consumers to spend the money on alternatives – like DPC – if they wish.

- Health care prices should be more transparent.

More details on these principles can be found in the full chapter.