Posted 2:45 p.m. Friday, Dec. 1, 2023

The Esau Johnson Collection

By Teri Holford (she/her)

November is the time of year when many cultures honor their ancestors. Altars, incense, flowers, food, offerings, services, poetry, song, theater, t-shirts…the traditions have varied throughout history. There is, however, one additional way to stumble across one’s ancestors: obscure archival collections you knew nothing about.

This is the story of how I recently met one of my ancestors.

For my late father, bedridden and in hospice, conversation was the only interactive activity left where he had complete control. So close to the end, he wanted to go back to the beginning, relive the past, talk about his childhood. Together, we mulled over the genealogy folders he had created and maintained over the years. I looked through countless photos, documents, family trees and letters back and forth between distant family members I had never heard of. Scattered among the clutter were pieces of torn paper with handwritten notes about a certain Esau Johnson. “First white settler in Monroe County. Made a fortune. Lost it all. Buried in a pauper’s grave near Sparta.” I remember groaning internally. Did I want to be connected to any of that? I asked my father about this person, whose particular first name was oddly connected to one of the most glaringly common last names around. He didn’t remember hearing much of anything about Esau Johnson. I looked back through the family tree and traced how we were connected. Maybe there had been more than one Esau Johnson born in 1800 in Guilford County, North Carolina and who had migrated to Monroe County and Southwestern Wisconsin during the early 19th century. My father didn’t know, couldn’t remember. I was confusing him. I could have dropped it, but I’m one of those who had pricked their thumb on the curiosity spindle. I was being tested. My quest took me straight to the Internet.

The thing about the Internet is that, combined with the vast wave of digitization that has taken place in the last couple of decades, genealogists are now very happy. People, places and events that had been hidden behind the analog curtain are now magically appearing. They pop up seamlessly in online searches, opening an entirely new array of resources without a need for fancy search terms. “Esau Johnson Monroe County” made up the handful of magic beans that I threw at Google. And those beans grew. Eyes wide and astonished, I looked through the results of newspaper articles, local historical society articles and vital records. There was only one Esau Johnson. And he was my great-great grandfather.

To top things off, while scrolling through the results, I saw that Esau’s personal handwritten memoir belonged to an archival collection. Looking closer, I realized I had access to that collection. It was part of the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS) archival collections housed throughout the state’s networks of Area Research Centers (ARC), to which UW-La Crosse Murphy Library belongs. Esau’s papers were housed at UW-Platteville’s ARC. Thanks to the archives transfer system between the WHS and all the ARCs, students, researchers, genealogists or any community member can request access to an archival collection and have it sent to the closest ARC. Seeing as the task of transferring ARC collections was part of my job at Murphy Library’s Area Research Center, I requested it.

The archivists at the UW-Platteville ARC informed me that this was one of their more popular archival collections that people requested. Esau’s memoir was an incredibly detailed account of life in Southwestern Wisconsin during the early and mid-19th century, before and after Wisconsin became a state. It was a very useful primary source for history students and others interested in life at that time in this region, and it was currently being used by a researcher. I’d have to wait.

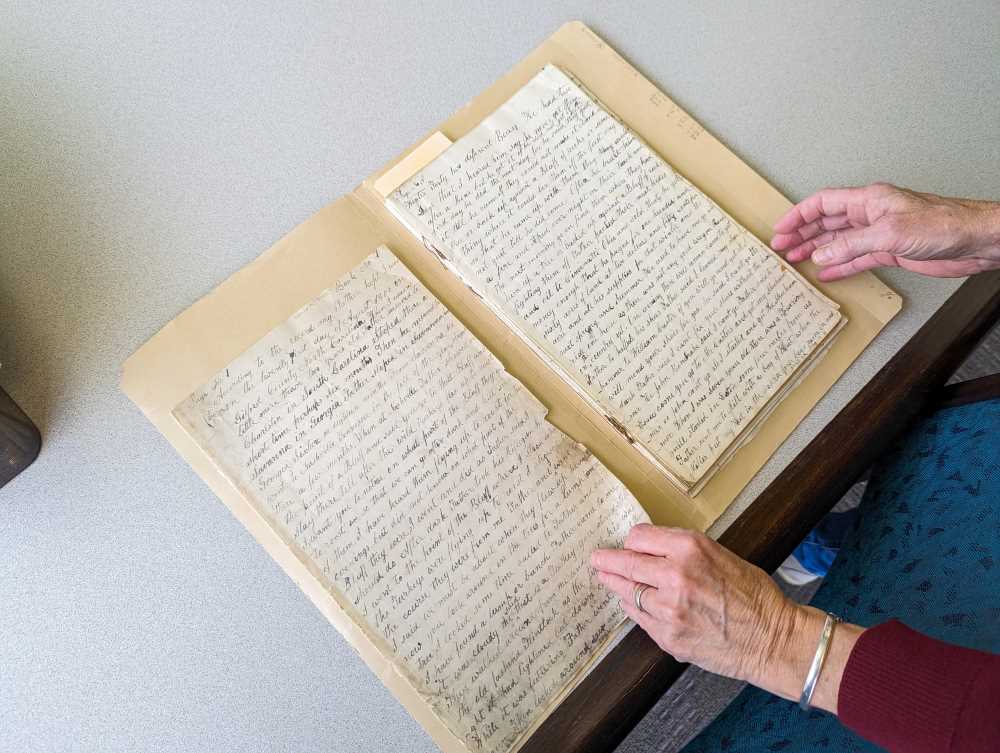

When the collection finally arrived, my hands opened up the transfer bin, and I removed the three boxes gingerly. That is a very strange way to meet someone related to you. As I made my way through the pages and pages of cryptic cursive, consulting the typed transcript only when absolutely necessary, I admired Esau’s drive to document his ordinary daily life over so many years, describing mostly uneventful events and encounters that now seem extraordinary to our 21st century eyes. Compared to other past figures who had made a bigger and fancier name for themselves through battles, politics or literature, there was nothing particularly flashy about Esau Johnson. Except that this kind of history is the people’s history.

Howard Zinn, a celebrated historian who championed people's history, said it like this: “A people’s history flips the script. When we look at history from the standpoint of the workers and not just the owners, the soldiers and not just the generals, the invaded and not just the invaders, we can begin to see society more fully, more accurately.” This is why seemingly trivial traces of our lives should be preserved. Workers, women and all historically underrepresented groups have their story to tell. Remembering this shifts our view of the underrated value in Grandma’s shopping lists, someone’s personalized scrapbook or a parent’s notebooks and letters. Not everything that has ever been written was done so with the intent to be publicly consumed, scrutinized or used for homework. A debate about the ethics of using historical personal writings will not solve the argument either, but the conversation is important.

Besides honoring our ancestors, November is also a time to be grateful as the harvest season is over and we prepare for the dark months. I’m grateful for the various people who found Esau Johnson’s papers, kept them and recognized the historical value by donating them to the Wisconsin Historical Society back in the 1950s, where they have been preserved. I’m grateful for digitization and the ability to access the record that led me to the actual papers. And I’m especially grateful for the very peculiar opportunity to have met my great-great grandfather, Esau Johnson.