Posted 4:45 p.m. Friday, May 11, 2018

Compared to a musician’s master class, these biochemistry students receive feedback from peers weekly, revise studies, apply knowledge and present.

Compared to a musician’s master class, these biochemistry students receive feedback from peers weekly, revise studies, apply knowledge and present

The first day of Chemistry 419, professors Dan Grilley and Todd Weaver tell students what they can expect after college. “No one is going to have you solve an equation on the board. They assume you know how to do that,” says Grilley. “It’s the soft skills you know: How to write, speak, do teamwork, analyze data, critically think … that’s what matters.” And so Grilley and Weaver don’t ask their students to solve equations in CHM 419: Advanced Biochemistry Lab — or listen to them lecture. Instead, the students are the ones doing the majority of the talking. Students start the course with only a description of a research question they will need to answer based on scientific results from students who took the course the previous year. Then, in teams of three, students develop their own research project that will build on that story. Throughout the semester they collect and analyze novel sets of data that will be developed into a peer-reviewed manuscript and ultimately contribute to the scientific body of knowledge on a particular enzyme — alkaline phosphatase. “You’re used to a professor holding your hand and walking you through a course — getting a specific list of things to do and then doing them,” says Junior Roman Schlimgen, a biology and biochemistry major. “In this class you’re given a long-term goal, and you rely on your knowledge to accomplish it.” Students say the course draws on information they’ve learned in previous courses and, in particular, technical skills they learned during a fall semester prerequisite.A flipped model

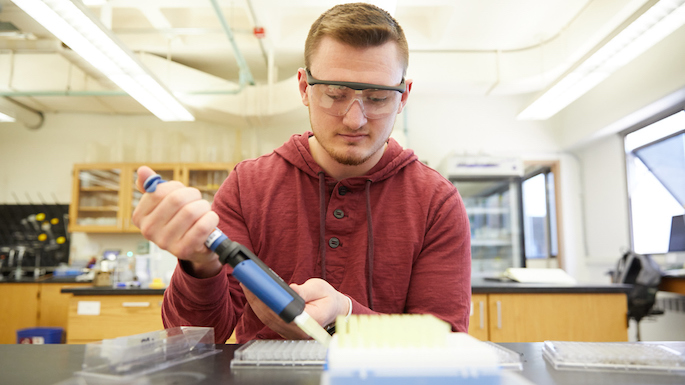

Weaver and Grilley developed CHM 419 — considered a course-based, undergraduate research experience or CURE — about five years ago and its format has changed dramatically. Their first attempt involved a class discussion, which typically resulted in them lecturing to the class. Today they’ve completely flipped the format — challenging the students to derive meaning from their research results and explain it to professors and other students through weekly presentations. “That switch between models of instruction was so critical,” says Grilley. “It forced them to think about the big picture ideas of their project.” Students are either presenting or providing feedback on another group’s presentation once a week related to their research projects. All of the projects are different, but together they tell the story of a particular protein enzyme — its properties and how it performs as those properties change. Weaver compares the course to a master class in music — where an artist performs a song and then learns how to improve based on feedback. “Musicians and artists are constantly getting feedback about their work,” says Weaver. “That’s what is missing in the sciences, and I think that has helped our students develop.” [caption id="attachment_52196" align="alignright" width="350"] Juniors Shanna Weber working in CHM 419. The course-based undergraduate research experience or CURE encourages students to learn soft skills through researching novel information, analyzing information and presenting results. Students in the course are looking forward to futures in a variety of fields from medicine to pharmacy to biomedical research.[/caption]

Also listening to other students’ presentations has led teams to reinterpret their own data. “When something doesn’t go exactly right, you have to problem solve your way out of it … maybe you’re miscalculating and will need to redo the experiment,” says UWL junior Shanna Weber, biochemistry and molecular biology major. “You learn through the experience.”

Students’ development over the duration of the course is evident. The instructors have received comments from graduate program instructors that some of their recent graduates are the best they’ve ever seen. They want more from UWL. Madeline Brunner, who took the course in spring 2017, was “obviously well trained” and is “making a big impression here with her work,” one instructor wrote to Grilley.

Mitch Malecha, a graduating senior and biochemistry major, is bound for medical school with a significant scholarship. He says CHM 419 was particularly helpful.

“Our core structure at UWL does a phenomenal job of preparing students for the next step,” says Malecha. “Doing research for four years and taking the classes I did, I learned a lot of information, but more importantly, I learned how to study and apply those skills.”

Grilley was invited to share information about the course, its construction and goals at an educational session of the Experimental Biology in San Diego in April. The annual meeting of five societies was comprised of more than 14,000 scientists and 25 guest societies.

Three of Grilley and Weaver’s 419 students brought home awards at the meeting’s poster session, more awards than any other school present, which included world-renowned research institutions.

“A lot of people said they came to our talk because they saw our students present at the poster session and thought we must be doing something right,” says Grilley.

Juniors Shanna Weber working in CHM 419. The course-based undergraduate research experience or CURE encourages students to learn soft skills through researching novel information, analyzing information and presenting results. Students in the course are looking forward to futures in a variety of fields from medicine to pharmacy to biomedical research.[/caption]

Also listening to other students’ presentations has led teams to reinterpret their own data. “When something doesn’t go exactly right, you have to problem solve your way out of it … maybe you’re miscalculating and will need to redo the experiment,” says UWL junior Shanna Weber, biochemistry and molecular biology major. “You learn through the experience.”

Students’ development over the duration of the course is evident. The instructors have received comments from graduate program instructors that some of their recent graduates are the best they’ve ever seen. They want more from UWL. Madeline Brunner, who took the course in spring 2017, was “obviously well trained” and is “making a big impression here with her work,” one instructor wrote to Grilley.

Mitch Malecha, a graduating senior and biochemistry major, is bound for medical school with a significant scholarship. He says CHM 419 was particularly helpful.

“Our core structure at UWL does a phenomenal job of preparing students for the next step,” says Malecha. “Doing research for four years and taking the classes I did, I learned a lot of information, but more importantly, I learned how to study and apply those skills.”

Grilley was invited to share information about the course, its construction and goals at an educational session of the Experimental Biology in San Diego in April. The annual meeting of five societies was comprised of more than 14,000 scientists and 25 guest societies.

Three of Grilley and Weaver’s 419 students brought home awards at the meeting’s poster session, more awards than any other school present, which included world-renowned research institutions.

“A lot of people said they came to our talk because they saw our students present at the poster session and thought we must be doing something right,” says Grilley.

Hard work pays

[caption id="attachment_52194" align="alignnone" width="685"] Junior Jason Toshner, a biochemistry and microbiology major.[/caption]

Many of the 419 students attest it is the hardest course they’ve taken at UWL, but they also agree it is worth the effort. Reading job descriptions in the biochemical sciences, students say the requirements are all things they’ve done — whether the more technical research skills or broader skills in communication and critical thinking.

They appreciate the dedication of professors who challenge them to reason through problems instead of simply providing an answer.

“They are very passionate about their work,” says Junior Jason Toshner, a biochemistry and microbiology major. “This is a capstone class so they expect a lot out of us, but having that high expectation makes us better scientists.”

Grilley and Weaver say the course does require a lot of mental bandwidth. Eight separate projects run concurrently and produce new results continuously. But they, too, find it rewarding.

“It is so amazing to watch students grow exponentially during the semester,” says Grilley. “They leave here with the skills most gain a year or two after they graduate.”

The class has given students a deep appreciation for scientists and the body of knowledge they’ve created. “You realize someone else had to put a lot of work in to get the results they did,” says Schlimgen.

Along with Weaver and Grilley, two other professors teach the course: Kelly Gorres and John May.

UWL’s biochemistry major was accredited by the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB) in January 2017.

Junior Jason Toshner, a biochemistry and microbiology major.[/caption]

Many of the 419 students attest it is the hardest course they’ve taken at UWL, but they also agree it is worth the effort. Reading job descriptions in the biochemical sciences, students say the requirements are all things they’ve done — whether the more technical research skills or broader skills in communication and critical thinking.

They appreciate the dedication of professors who challenge them to reason through problems instead of simply providing an answer.

“They are very passionate about their work,” says Junior Jason Toshner, a biochemistry and microbiology major. “This is a capstone class so they expect a lot out of us, but having that high expectation makes us better scientists.”

Grilley and Weaver say the course does require a lot of mental bandwidth. Eight separate projects run concurrently and produce new results continuously. But they, too, find it rewarding.

“It is so amazing to watch students grow exponentially during the semester,” says Grilley. “They leave here with the skills most gain a year or two after they graduate.”

The class has given students a deep appreciation for scientists and the body of knowledge they’ve created. “You realize someone else had to put a lot of work in to get the results they did,” says Schlimgen.

Along with Weaver and Grilley, two other professors teach the course: Kelly Gorres and John May.

UWL’s biochemistry major was accredited by the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB) in January 2017.