Going for gold

Alums, faculty reflect on their Olympic experiences

no cutline needed

Posted 5:48 a.m. Wednesday, July 21, 2021

One helped manage the feud between figure skaters Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan.

Another sprinted his way toward Olympic gold just two months after graduating.

Through the decades, UWL representatives in the Olympics have coached, competed or contributed otherwise.

Before the Summer Games kick off July 23 in Tokyo, here’s a look at how a few of the many UWL Olympian-affiliate alums and faculty left their mark on the world’s greatest sporting event.

Curling provides straight path to the Games

When the International Olympic Committee announced Salt Lake City would host the 2002 Winter Olympics, Robert Richardson and his wife, Silvana, knew they wanted to experience the Games — but not as spectators.

Richardson, then a professor of educational studies with an athletic background in luge and curling, showed up at Olympic headquarters in Salt Lake City looking for a role. They had one for him — sport administrator of curling — but it came with a catch. Due to extensive on-site responsibilities, he needed a Utah address.

Without batting an eye, he agreed. The couple purchased a condo to make it official.

As the curling sport administrator, Richardson’s job was to ensure the Olympics’ curling competition ran as smoothly as possible.

He helped create local curling clubs in Utah so he would have skilled curlers who could manage test competitions.

When the testing ended and the real matches began, he was responsible for making certain the officials were in place, the flower ceremony was in order and a hundred other things were ready to meet demand.

Meanwhile, Silvana, a professor of nursing at Viterbo, headed up the curling medical team.

In addition to their roles, they both pursued post-doctoral study at the University of Utah

Richardson says it was an intense time, but also rewarding and memorable.

He had lunch with Kristi Yamaguchi, frequently bumped into Salt Lake Organizing Committee President Mitt Romney, and even got to carry the Olympic flame through Eagle, Colorado.

“It was electric,” he says. “I can remember every moment of it.”

The Olympic experience was well worth the price of a condo, Richardson says. The couple maintains it in hopes that Salt Lake City will host the Winter Olympics in 2032.

Read more

Find out more about the Richardsons’ Olympic experience in the podcast

The speed skating scientist

Carl Foster and speed skating were an unlikely pair, but they couldn’t have been a more perfect match.

A Texas native with no previous knowledge of the sport, Foster fell into the world of speed skating after beginning his career as an exercise and sport scientist at Sinai Samaritan Medical Center in Milwaukee.

Foster spent time at the oval in Milwaukee, where many top speed skaters trained with their coaches. He absorbed everything he could and soon realized the sport was relatively unexplored by scientists and researchers.

In the runup to the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, Foster was giving advice to U.S. speed skaters and coaches, hoping to give them an edge. The American skaters racked up five gold medals and eight overall medals during the 1980 Games — both more than any other country.

In the years that followed, Foster became a fixture of U.S. speed skating, using cutting-edge science to help the country’s top skaters perfect their craft.

He went on to chair the Sports Medicine/Sports Science/Drug Testing committee for U.S. speed skating and received a research grant from the International Olympic Committee to conduct studies (along with fellow UWL professor John Porcari) at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.

By the time he scaled back his involvement in the mid-2000s, Foster had built a reputation as one of the sport’s most influential scientific minds. He was elected to the U.S. Speed Skating Hall of Fame in 2020.

“It was a pleasant surprise, because there aren’t many non-skaters like me in that club,” Foster says of the hall of fame. “This is a nice pat on the back, and everyone likes a pat on the back.”

Read more

See more about Carl Foster’s entry into the U.S. Speed Skating Hall of Fame

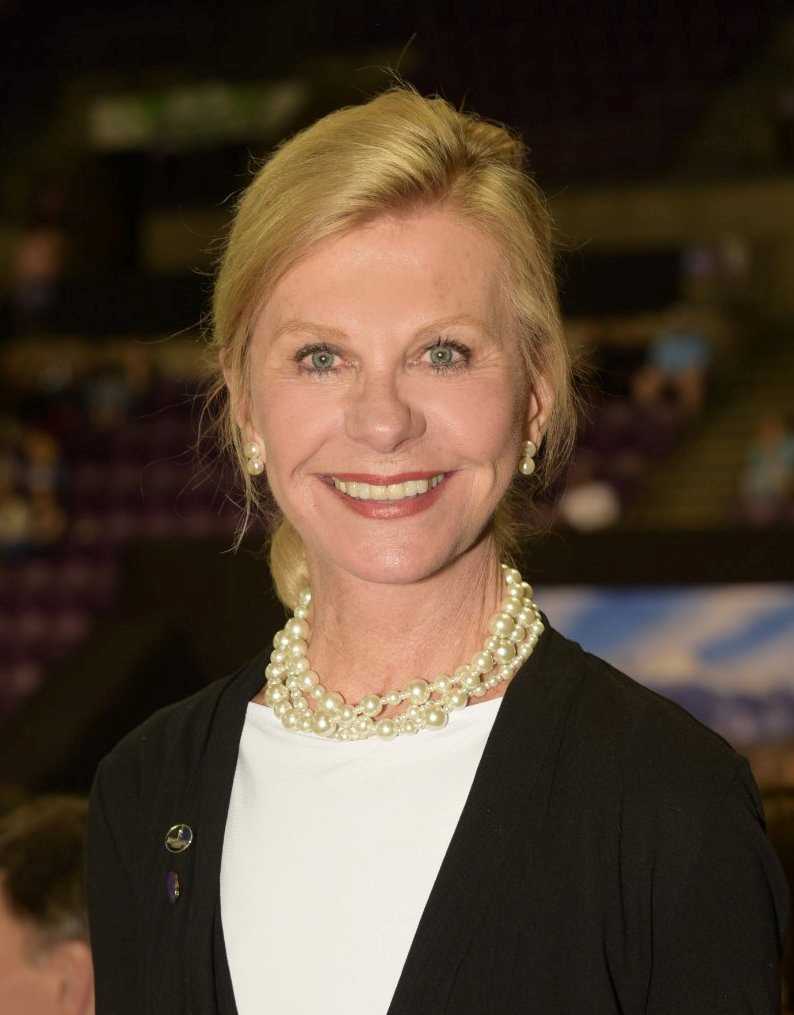

An icon on ice

Gale Tanger owes her career in figure skating, at least in part, to her fashion sense.

Growing up, she admired the bright white skates figure skaters wore on TV.

“I’d been speed skating since I was five or six, and I told my dad I wanted to wear white skates,” recalls Tanger, ’68. “But my dad told me that speed skaters wear black skates, and figure skaters wear white skates. Eventually, my parents bought me white skates and gave me figure skating lessons.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Over the past 50 years, Tanger has built a reputation as one of the most influential and innovative voices in the world of figure skating. She has judged countless international competitions, built lasting friendships with the sport’s brightest stars, and held key leadership roles in several Winter Olympics.

For the 1994 Winter Games in Lillehammer, Norway — her father’s home country — Tanger served as the U.S. team leader for figure skating. One unexpected task was managing Tonya Harding’s infamous feud with Nancy Kerrigan and the public relations crisis that ensued.

“Even though there were challenges with Tonya and Nancy, it was an incredible opportunity and a great Olympics,” she notes. “And it was such a great place for it. Where else could you have such a pristine Olympics? The snowflakes were like diamonds coming out of the air. To me, it was just wonderful.”

Another highlight came in 2002 in Salt Lake City, when Tanger was assistant chef de mission of the entire U.S. Olympic Team. It was a thrill, she says, to serve during the Olympics in her home country.

In recognition of her outstanding career, Tanger was named to the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 2021.

Read more

Learn more about Gale Tanger’s decades of involvement in Olympics Figure Skating

Running for gold

Andrew Rock had one shot at Olympic glory.

He made the most of it.

Rock, ’04, UWL’s only Olympic gold medal athlete, achieved that feat in the men’s 4x400m relay at the 2004 Summer Games in Athens.

He had spent the preceding months working with UWL’s track and field coach, Mark Guthrie, trying to peak for the Olympic trials in Sacramento. Rock placed sixth, good for a spot on the team.

Several weeks later, the fresh-faced college grad was absorbing the dreamlike spectacle of the opening ceremonies.

“That’s when it hit me that I was at the Olympics,” he recalls. “I mean, I was a kid from a town of 1,500 people, a D3 school. It was surreal.”

Before the qualifying heat, with 80,000 fans packing the stands, Rock thought about something Guthrie had said: “This might not feel like just another race. But the moment you get the baton, it’s exactly the same.”

Rock, the third leg of the American team, upheld his end of the bargain, advancing the United States to the medal round. The team cruised to victory in the final, earning the gold.

“It’s one of those things where the competition is so tough, you don’t want to let your mind go there,” he explains. “Then when it’s over, it’s like: ‘Wow! We just won the gold medal!’”

Rock, who now coaches at Bethel University in Saint Paul, ran competitively for several more years but never qualified for another Olympics.

His Olympic moment may have been fleeting, but it was much bigger than a single race.

“I only ran for 44 seconds at the Olympics, but I poured my life into those 44 seconds,” he says. “I learned a lot about myself just trying to get there.”

Read more

Andrew Rock reflects on his Gold Medal experience at the ’04 Olympics

See how Andrew Rock continues to pass on Olympics lessons in his current coaching position

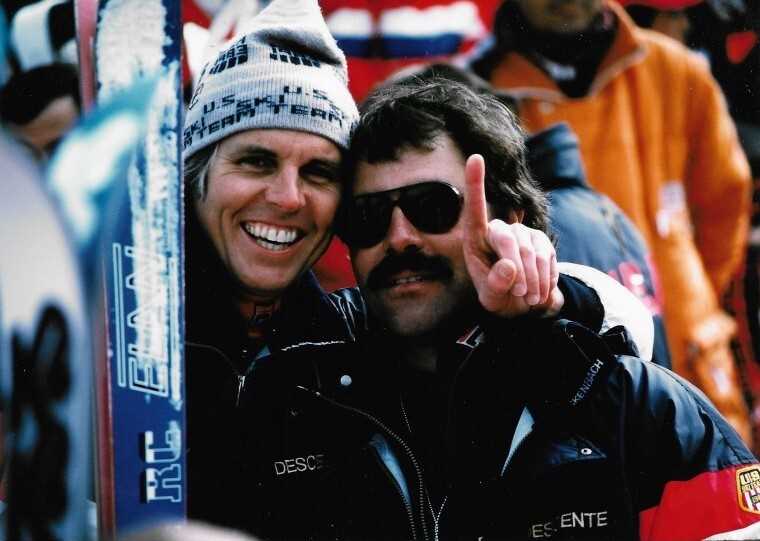

Skiing goes anywhere but downhill

Topper Hagerman used an unorthodox approach to prepare the U.S. men’s alpine ski team for the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo: He got them off the snow.

As the team’s trainer, Hagerman, ’68, made sure the skiers had plenty of time on the slopes with their coaches. But for training, he kept things fresh and engaging by introducing them to water polo, basketball and football.

“I had the opportunity to basically set up my own programs,” Hagerman explains. “It was a lot of fun. They spent so much of their lives on snow. I wanted to give them a break from it.”

Hagerman, who had a sports physiology background, was also responsible for treating injuries. Remarkably, in a sport that involves hurtling down icy slopes at 70 mph, the team had no significant injuries leading up to the Olympics.

Shortly after the Games began, a snowstorm swept into Sarajevo, cancelling the first two days of downhill training.

Some of the European teams, wanting to stay sharp, returned home to practice.

Hagerman, staying true to form, had a different plan.

“We found a basketball court, and I told the guys, ‘Full court, let’s go,’” he remembers. “All these other teams flew back to their towns, and here we were playing basketball. That’s just what we did. We were a little bit different.’”

It’s hard to argue with the results.

The U.S. men had a breakout performance, claiming three medals — two golds and a silver — after winning just one in 1980.

“We were very excited with everything that happened,” Hagerman says. “It was quite the experience for us.”