Posted 1:07 p.m. Wednesday, April 12, 2023

UWL expert explains lack of female statues in public art in the U.S.

If you were walking around American city streets looking for clues about the country’s past, you might think that history was based almost entirely on men. Only 6 % of statues in the U.S. are of real women, according to UW-La Crosse Art Professor Sierra Rooney. In addition, statues of allegorical figures of women – those that represent ideas like liberty and peace, but not real women — are more prevalent than real, named representations.

The Wisconsin state Capitol grounds will help reverse this trend when its first statue commemorating a prominent Wisconsin African American trailblazer Vel Phillips is likely to be placed in 2023 or 2024. A campaign is currently underway. Likewise, other city projects in diverse sections of the country have placed more women from history in public art from San Francisco to New York City.

Below, Rooney, who studies public art, monuments and memorials of the U.S. and is developing a database of monuments to women, answered questions about the dearth of female statues and the movements to change the tide.

How many statues in the U.S. are of women?

There are around 300 statues honoring real women in the U.S. compared to around 5,000 statues honoring real men in the U.S. Only 6% of American monuments feature real women as their subjects.

Why are there so few women monuments?

During the mid-to-late 19th to early 20th centuries, America experienced an intense period of monument building where primarily elite, Anglo-Saxon men were put on pedestals. So many monuments were built during this era that newspapers called it “monument mania” and recounted a public fear that the streets were being overrun with statues.

Although more than a century has passed since this period, the bias of many more elite, male monuments is still reflected in public art today.

Of the top 50 represented individuals in U.S. statues:

- 11 are U.S. presidents

12 are U.S. generals

50 % are men that enslaved other people

40 % were born into a wealthy family

(Data from Monument Lab. Note: While Monument Lab data does not include every U.S. monument, it is the best current source of data for monuments across the U.S.)

Why are monuments significant and why should we care about this gap?

Monuments are not history. They are interpretations of history by people who determine what and whom are important of honoring.

These concepts, people and events honored on pedestals across the country are built-in reminders of what people think are worthy of enshrining. Within the current monumental landscape, the idea of a hero has been largely conceived to be a wealthy, elite white male. It is not representative of the vast contributions of women, the LGBTQ+ community, Hispanics, Black, Asian and Indigenous people.

How are monuments around the U.S. officially tracked?

Because monument-building is so decentralized and often exists outside traditional collections like museums or archives, there is no comprehensive, up-to-date source for data collection.

In 2021, Monument Lab, an organization dedicated to creating more diverse and inclusive public art, did the most comprehensive audit of monuments in the U.S. But even this is incomplete, and there are many omissions. For example, the statue of Ellen Hixon on the Bluffs in La Crosse, Wisconsin, does not show up on the Monument Lab map.

Part of Rooney’s research involves tracking down monuments to women. She has been keeping a database since 2016 using an array of sources.

Most famous female statue?

One of the most famous statues to women is the Portrait Monument that’s in the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C. The statue, which honors suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was sponsored by the National Woman’s Party in honor of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

It remains an unconventional monument: the heads and shoulders of the three busts of Mott, Stanton, and Anthony seem to emerge from a massive, eight-ton rough-hewn Carrera marble block. The artist Adelaide Johnson purposefully left the block incomplete to symbolize that work of the women’s rights movement was unfinished.

The unveiling ceremony for the monument was held in the Capitol Rotunda in 1921 on the 100th anniversary of Anthony’s birthday and was attended by representatives of over 75 women’s organizations. But just 24 hours later, a group of congressmen had the monument unceremoniously moved to the basement, to a space known as the “Crypt.” Here it earned the derisive nickname: “Three old ladies in a bathtub.”

It remained in the Crypt for decades, until consistent lobbying efforts by a coalition of women’s groups finally spurred the monument to be moved back to its prominent place in the Rotunda in 1997.

More recently, you can see the Portrait Monument in the background in many of the photos from the Jan. 6 riot in the Capitol.

What woman has been represented the most in monuments?

Joan of Arc is the most represented women in statues in the United States, which is ironic because she wasn’t American. Harriet Tubman is the second most honored women in the U.S., followed by Sacagawea, Rosa Parks, and Sojourner Truth.

Allegorical figures of women are more frequently represented than real, named women. For example, according to the Monument Lab data, there 22 sculptures of mermaids to 21 honoring Tubman (though the number of monuments to Tubman have increased since the audit, so she’s pulled ahead!)

When unnamed, what do statues of women represent?

Going back to late 19th and early 20th century period of monument mania, figures of women in monuments served allegorical roles such as symbolizing peace, liberty, loyalty, vice and justice. Think of the frequently-used symbol for justice being the female figure holding a scale.

Two allegorical monuments of females most prominent in the U.S. both symbolize freedom: the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor and the Statue of Freedom at the top of the Capitol in Washington D.C.

Sometimes monuments combine allegorical figures of women with figures of real men. In New York City, for example, there is a gilded monument depicting the union victory in the American Civil War features General William Tecumseh Sherman, the union general, sitting on a real historical horse (we know the horse’s name!) He is led by an allegorical figure of victory. The statue of victory was based on a Blac-woman model, Hettie Anderson, but she is not named in the statue nor is she intended to have a specific identity. Instead, she serves as a symbolic prop to Sherman’s accomplishments.

What do you encourage monument builders to do when considering a new project?

This is an exciting time because there is a lot of public discussion and debate around greater diversity in monuments across the globe. Anyone considering a new project should consider how monuments contribute to greater racial justice and gender equity. How can monuments reflect the beautiful plurality of this country?

Don’t just think about who is represented but how they are represented. It is not just the subject matter in a monument that is important, but also the way that the story is told. For example, when you think of a typical monument, you probably think of a large bronze statue sitting on a pedestal. This type of monument originated in ancient Rome when leaders would erect portraits of themselves as propaganda to establish their authority. Standing high on pedestals these powerful figures were intended to be literally and symbolically looked up to. This has served as the model for monuments for thousands of years.

But this is antithetical to the more democratic ideals of today. Monuments should be reflective of this change and be more expansive, more engaged and reflective of communities. A great example of a new kind of monument that is not just a person on a pedestal was unveiled last week with the monument to Harriet Tubman in Newark, New Jersey. It replaces a long-standing statue of Christopher Columbus. Harriet Tubman is known for liberating people in the south. She has 21 statues in the U.S. The majority depict her role with the underground railroad, but her life was long and full. After the underground railroad, she served in union army as cook, was the first woman to lead a military expedition, joined the national women’s suffrage movement, and established a hospital for elderly and sick Black Americans. She had a rich life full of remarkable accomplishments, but all of these other contributions are absent from her monuments. In this new monument, it is not a single statue, but a space you can enter. It is a large circular lane wall with stories of her entire life and it features a likeness of her face. It also includes stories of Newark’s Black liberation movement and mosaic tiles designed by Newark residents. The monument connects the legacy of Harriet Tubman with the community of Newark today.

What is the significance of the placement of a monument?

Anytime a monument is raised up, we symbolically look up to it. By bringing a monument down to ground level, we create the impression that we are on the same level as them. Monuments are in public spaces, so we should be able to interact with them: touch them, throw an arm around them, and take pictures with them.

Think of placement in terms of their level and where on the site it is. If you put a monument where the subject worked or lived, that can be powerful. Vel Phillips statue on the Capitol grounds in Madison is a more meaningful site for that statue than to be a random park because it conveys the impact of her political work.

When did we start to see an increase in monuments for women?

We see a marked increase of statues of women beginning in 1980. This was part of a larger effort to include the voices of women into the history of the U.S. 1980 was also the year of opening of the Women’s Rights National Historic Park in Seneca Falls, New York — the first national park honoring women — and the establishment of National Women’s History Week, which eventually became National Women’s History Month in 1990.

In the last few years, we’ve seen another sharp increase in monuments to women. This is in large part of result of the activism of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. #MeToo gave rise to a dialogue about women’s empowerment and the vital importance of equal representation more broadly.

In the summer of 2020, protestors around the world began defacing, beheading, and toppling monuments with racist and colonialist histories, including those honoring Confederate soldiers and generals and Christopher Columbus. These actions were spurred by the BLM protests against police brutality and specifically the murder of George Floyd. Public monuments quickly became vectors for reckoning with a racist past and present. This has prompted communities across the country to call for the replacement of monuments to historic figures with complicated, and often troubling legacies with monuments that honor previously marginalized or underrepresented subjects.

What initiatives have happened state and nationwide to change this gap?

- SheBuiltNYC, which received $10 million in city funds to commission new public art works honoring women important to the city, like Shirley Chisolm Billie Holiday, Helen Rodríguez Trías, and Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson.

- San Francisco, which passed an ordinance in 2018 that required 30% of new artworks installed depict real women.

- The National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, which is a microcosm of commemorative patterns national wide, has also seen several new women enter the Hall. Each state in the union can donate two statues of notable residents to the hall. Representative of the figures deemed important at the time — presidents, politicians, military leaders. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s historically been dominated by white men, some who are not well remembered today. Wisconsin honorees are: Jacques Marquette, French Jesuit missionary and explorer, donated in 1897 & Robert M. La Follette governor in 1900, he proposed and implemented his "Wisconsin Idea, donated in 1929

- To increase diversity of representation, Congress passed a bill in 2000 that allowed states to replace their previously donated statues in the hall. Last year, Florida replaced its statue of Confederate leader, with statue of Mary McLeod Bethune, and Kansas donated a statue of Amelia Earhart. And there are several more statues of women currently in the works.

- In Madison, there is a campaign to place a statue of Vell Phillips, the civil rights activist and the first Black individual elected to statewide office in Wisconsin and the first Black judge in the state, on the ground of the Capitol. The statue could be the first African American woman to have a statue at any capitol in the U.S. outside of Rosa Parks at the U.S. Capitol building.

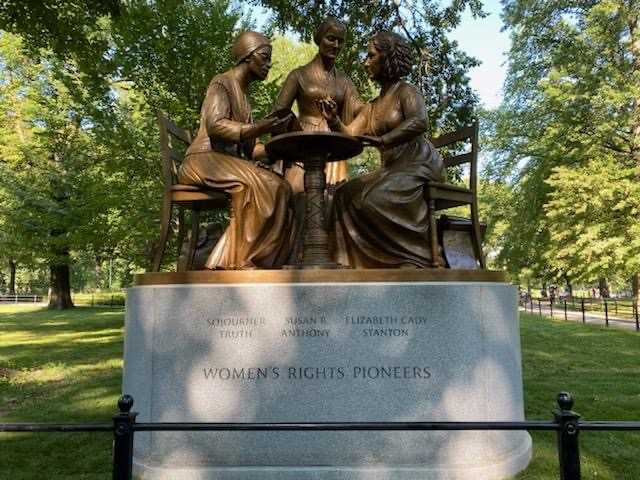

- Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument: Until 2020, New York City’s Central Park — one of the most visited spots in the city — had 22 statutes dedicated to male historical figures but no statue dedicated to a real woman from history. Statues dedicated to fictional characters were also part of the park’s art including Mother Goose and Alice in Wonderland, and even a statue to a dog, Balto. In 2020, a monument of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Sojourner Truth was dedicated on the centennial anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment.

What is the difference between a monument and a memorial?

Monuments and memorials are sculptural or architectural works that mark and honor the past. These words are often used interchangeably. but I think it’s helpful to distinguish them.

Monuments celebrate. Their tone is triumphant. They are a physical manifestation of a hero or a military victory. An example of this would be the Washington Monument on the National Mall.

Memorials commemorate. Their tone is somber. They express loss from war or disease or remember a tragic event. An example of this is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Wall.

More resources on women monuments coming

Sierra Rooney teaches art history at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. She is currently working on a book about monuments to women in the U.S. Accompanying this will be an open-access database and a digital map.

An example of her methodology can be seen in her most recent article, “Commemoration of an Epoch: Monuments to the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States,” which was selected as the inaugural project for the “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,” a initiative funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and administered by Panorama: The Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, that supports accessible digital art history scholarship that focuses on the contributions of constituencies that have historically been marginalized or under-researched. Rooney's research has also been featured on Wisconsin Public Radio.